I’m currently reading Alexis de Tocqueville’s classic,Democracy in America. Tocqueville was a

Frenchman; he wanted to write a book that would help French leaders incorporate

democratic principles in France’s new constitutional monarchy. To do this, he came to America and studied

our young democratic government. He

toured the United States reading, interviewing, and generally learning

everything he could about American history, government, and culture. He published his book in 1835 (an English

translation was published in the US in 1838).

It is a fantastic read: I’m very

impressed with the wisdom I’ve found in this book.

|

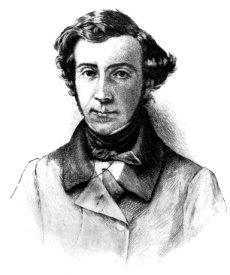

| Alexis de Tocqueville Photogavure from the 1899 edition of Democracy in America Source: Wikimedia Commons |

This caught my attention, as I’ve often wondered this very

thing. From the perspective of me living

in 2014, slavery is so abhorrent, so obviously wrong, that it seems completely

irrational that someone living 200 years ago would consider owning another

person. Yes, the culture was different,

but white southerners were still living in a Christian society, believing in the Bible. Abolitionists preaching the immorality of slavery were all over the place. Slavery had already been abolished in much of

the world long before America got around to it.

How, then, did slaveholders justify to themselves what they were doing? How did they rationalize their behavior?

Tocqueville’s explanation was very interesting. According to him, slaveholders didn’t

rationalize their behavior, exactly.

They were Christian, and they weren’t stupid. They knew slavery was wrong. They knew it wasn’t economically efficient. Trouble was, they didn’t know what to do

about it. Slavery was so deeply

ingrained into the economic structure, legal system, and culture of the

American South that they couldn’t root it out.

Here’s an example of the difficulty:

“I happened to meet with an old man, in the South of the

Union, who had lived in illicit intercourse with one of his Negresses, and had

had several children by her, who were born the slaves of their father. He had indeed, frequently thought of

bequeathing to them at least their liberty; but years had elapsed before he

could surmount the legal obstacles to their emancipation, and in the mean while

his old age was come, and he was about to die.

He pictured to himself his sons dragged from market to market, and

passing from the authority of a parent to the rod of the stranger, until these

horrid anticipations worked his expiring imagination into frenzy. When I saw him, he was a prey to all the

anguish of despair; and I then understood how awful is the retribution of

Nature upon those who have broken her laws.”

(Page 318).

That was honestly one of the saddest things I have ever

read. I think human nature leads us to

expect that people who want to do good things will be able to accomplish them

if they work hard. Instead, this was the

story of a man who tried very hard to do the right thing and couldn’t. Tocqueville predicted that the only way to break

and end slavery in the United States would be through war. Tocqueville was right.

1

After reading this section of Tocqueville, I find myself in

the odd position of feeling compassion for a group of people who I’ve always

lumped into the “bad guys” category. Slavery

is absolutely, unequivocally wrong. It shouldn’t

have happened. But . . .

I know what it’s like to feel trapped by the consequences

from bad choices—my own or other people’s.

I’ve been in situations where I knew, or thought I knew, what the right

choice was, but as I struggled to do right realized that I didn’t have the strength or ability required to do it. I

emerge from these difficulties with an increased gratitude for the

Atonement. Christ’s grace can break the

bonds that keep us from accomplishing the good things we try unsuccessfully to

do. He can increase individuals' courage

and strength and he can send a nation a Lincoln.

Tocqueville, though, thought the war would come via a slave uprising,

similar to what happened in Demarara in 1823.

return

.jpg)